APPROACHES AGAINST THE FOSSIL FUEL FUNDAMENTALISM

An interview with Oliver Ressler by Dorian Batycka, with an intervention by Mike Watson.

Dorian Batycka: Your film that will be presented later this September as part of the Maldives Pavilion for 55th Venice Biennale, entitled Leave It in the Ground is not the first of your works that deal with climate change. Other projects including For A Completely Different Climate (2008), 100 Years of Greenhouse Effect (1996), and Sustainable Propaganda (2000) all comment on the contemporary discourse of climate change. What do you hope to achieve with Leave it to the Ground, and how does it differ from your other projects pertaining to climate change and ecological crises?

Oliver Ressler: Leave It in the Ground (working title) is based on a narration I am writing, drawing a line between global warming and uprisings, how disastrous weather conditions lead to the emergence of movements in various places, how old orders are toppling and open up possibilities that could lead to long-term social and political transformations, both good and bad. The film—which imagery was in part recorded in the seemingly idyllic landscape of the Lofoten archipelago in Norway—discusses climate crisis not as a technical problem, but as a political problem.

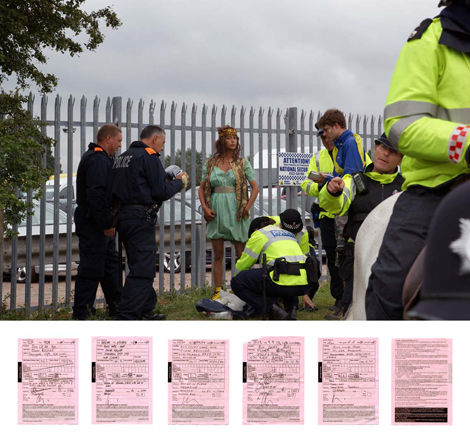

To compare this work with three previous works is quite a task, as all of them are different and related to very specific contexts at the times they were produced. 100 Years of Greenhouse Effect (1996) is a series of digital prints that relate to the first scientific proof of the existence of an anthropogenic climate change in 1896 through the Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius. In my work Arrhenius’ scientific text was intertwined with a critique on the dominant discourse dealing with global warming 100 years later, the technocratic concept of “sustainable development” launched in a book by the Wuppertal Institute for Climate, Environment, and Energy in 1996. Sustainable Propaganda confronts the same discourse on the occasion of the world fair in Hannover in Germany in 2000, which attempted to popularize “sustainable development” for a mass-audience. For A Completely Different Climate (2008) finally focuses on a newly emerging climate movement in the UK.

DB: Could you expand a little on why you decided to make Leave it in the Ground now, how you structured it?

OR: Today it is even more urgent to deal with the issue of global warming than 17 years ago, when I did my first piece focusing on global warming. Among scientists who take themselves serious it is not being discussed any more that global warming exists. But it is also clear today that the international treaties such as the Kyoto Protocol completely failed to achieve the required reduction of carbon dioxide emissions. They established an international emissions trading system that created a new market, but did not reduce emissions.

My guess is that the current capitalist system won’t be able to reduce carbon emissions to the required level; it will only react where it is necessary to guarantee the maintenance of the system, which does not necessarily imply that a basis of existence will be provided for all people on the planet—as it is already the case nowadays. The enormous environmental disasters in the recent years did not lead to a reduction of the emissions that are responsible at least in part for these disasters; the reaction was that the countries in the Global North encapsulate themselves, militarize border control, build walls to keep away migrants, who to a growing extent also migrate because their living conditions got destroyed in their countries of origin. Of course global warming is not the only cause for migration; the catastrophic impacts Free Trade has e.g. for peasants in the Global South is another central reason.

DB: The notion of sustainable development and green energy is a concept that strongly resonates with many environment activists and campaigners, but more recently those such as Bill Mckibben from 350.org have called for forms of divestment from carbon producing companies, and the need to create political economic models independent from dominant hegemonic energy interests. What role do you feel does political economy have in addressing climate change and global warming?

OR: In my opinion the main task today is to combine the discussion of climate change with the discussion of a need of a change of the economic and political system. Keeping intact the existing global power relationships but just introducing a bit of renewable energy resources won’t be sufficient. A monopolized energy industry will always offer centralized supply of power—even if it might be a bit greener in the future—in order to assure corporate profits. Therefore it is not only important to consider from which sources to produce energy, but also how to produce it. Who owns the means of energy production? I believe the struggle for a democratization of society also has to include the aim for a control over the means of production of energy—which should come primarily from renewable resources of course and have to be produced in a de-centralized way controlled directly by the people in the neighborhoods where the energy is being consumed.

In order to achieve this a strong political transnational movement will be needed that puts pressure on states, financial institutions and corporations; and divestment of course is a powerful, useful tool in this process.

DB: Capital and energy are inextricably linked. Capitalism manifests most explicitly through the conversion of raw materials and energy into commodities—from extraction through the delivery of the final product to the consumer—thereby generating profits. Countries and economic zones today strive for infinite growth potential and perpetually increasing GDP. As Professor Kütting from the State University of New York concluded, “this liberalization and its supporting institutional framework have led to a new form of ecological imperialism that subjugates resource extraction and production to market ideology.” Do you think that if we continue down this capitalistic road paved with models of infinite growth and GDP, like a cancer devouring its host, we will ultimately find ourselves subsumed within a violent form of ecological destruction?

OR: I think this violent form of ecological destruction already takes place today; maybe a bit less visible in the Global North, and much more visible in the Global South. In many parts in Asia and Africa desertification through climate change takes place here and now; through land grabbing large zones of agricultural land are being transformed through industrialized agriculture, destroying the land through pesticides, in order to produce bio-diesel for transport needs in the North, while peasants whose families have been living on the land for generations are being kicked out by paramilitary groups employed by the new “owners” of the land. Glaciers are melting. There are many more examples of course. The future already started, and it will be very hard to change this course of development before the level of ecological destruction and effects on people will further increase.

DB: What has been your greatest challenge thus far as an artist primarily engaged with issues concerning migration, economics and climate? Do you feel that this movement of socially engaged art and artists has (in some respect) been coopted by dominant interest groups and institutions?

OR: I am not sure we can talk about a movement of socially engaged art and artists. Just consider the gallery market, art fairs and large museums, and the marginal role political art plays in these dominant institutions. Therefore I also don’t see the problem of cooptation as a central one at the moment. I think we are rather still in the process of struggling for visibility for socially engaged art. I believe all these themes you mention, migration, economics and climate, are all somehow connected, even though the dominant discourse tries to discuss them as entities separated from each other for which specific, technocratic “solutions” are being introduced. My work is often connected to different social movements, and encouraging social movements that open up possibilities for how to deal with this multi-dimensional crises we are facing could be described as the greatest challenge.

DB: How might you imagine freedom in 140 characters or less (for the Twitter generation)?

OR: I guess this is such a complex theme, that probably 140 pages might still be insufficient, especially since the term “freedom” (similar to “democracy”) also got increasingly contaminated in the last two decades by conservative discourses and political fractions. But central to “freedom” as I wish to see it is that it does include the economic sphere, and of course there cannot be experienced freedom if you are forced to sell your labor force under capitalist relations, where a small group owns all the means of production and the majority does not.

DB: Austria has been flooding, the polar ice caps have been melting, violent storms and changes haven been happening everywhere, but everyone (including governments and citizens alike) seem content to go on despite all this, do you think climate change has become an existential crisis par excellence, to the point where people can no longer imagine a world without global warming?

OR: There are influential corporations lobbying a lot in order to hinder governments or super-national institutions such as the EU to take major steps away from this fossil fuel fundamentalism and keeping fossilized capitalism to remain in place. And the same governments that are completely impotent of developing a political agenda do their best to avoid any serious discussions about climate change that would necessarily point out their impotency. One must learn that the climate is a very relative thing: according to the politicians in power it must be compatible with economic growth.

Mike Watson: Any attempt to unify ecological and broadly anti-capitalist concerns can be seen as opportunistic in the sense that the left need not even believe in man made climate change in order to be supportive of its campaign to reduce industrial output. Yet, to cast ecological issues in a traditional leftist framework—i.e. as class exploitation—anthropomorphizes nature with its ‘suffering’ seen as linked to our societal suffering at the hands of capital. The only way around this is—as I see it—is a total embrace of ecology by the left to the extent of advocating a kind of naturalistic law, whereby relations then became subsumed under ecological ones, with exploitation of the worker seen as an ecological offence. In reality, nature will survive humanity and its political and economic systems. Humanity’s survival, however, is intrinsically linked with nature. Can you see this distinction, and how does your linking of ecology with capital relate to these thoughts?

OR: There are several examples for anti-capitalist struggles and practices with articulated focuses on ecological issues that go already back many years, and I believe there is no way to call them opportunistic: the self-government of the Zapatistas in the Lacondonian forests in Chiapas, the Guardia Indígena of the Nasa in the South of Columbia against the timber and mining industry, the transnational activities of the peasant organization Via Campesina, Murray Bookchin’s attempts to initiate ecological and self-managed communities in the U.S., the before-mentioned climate camp movement in the UK, Germany and elsewhere, to name just a few. All these are clearly anti-capitalist and ecological oriented at the same time, not because of opportunism, but because of an understanding that a serious implementation of ecological principles will have to shred the free-market ideology that has dominated the global economy for more than three decades, as a serious response to climate change requires the break of every rule in the free-market playbook. There are ecological reasons for a systemic change, there are political reasons for a systemic change, there are social reasons for a systemic change. All these reasons have to be taken into consideration when the power relationships will change some day and it will become time for people to democratically decide how they wish to develop new structures, institutions and relations of living together. I don’t see a danger of subordinating life to certain boundaries of nature at all; I only see the danger in the consequent ignorance of boundaries the current system inherits. Of course, this naïve paradigm of perpetual economic growth cannot play any role in a future democratic system that among many other principles has the limitation of anthropogenic global warming as a central goal. The necessity for climate change is one of the most powerful arguments against capitalism, and I believe this still needs to be pointed out more clearly in future struggles.